I’ve gone off on one before about the why’s and wherefore’s of being more intelligent about your CSS architectural choices, so I’ll save the long chat, and just assume you’re onboard with the whole idea of styling mostly with classes, tiers of styling specificity, and focussing on reuse.

When I’ve spoken to non-CSS developers, the big concern around updating or removing features from a stylesheet is the worry that other pages that make use of the same styles are adversely affected. This concern then leads to either the developer in question considering CSS to be a “Dark Art” - something that it really doesn’t need to be.

Cascading Stylesheets Gonna Cascade

A lot had already been said about using certain patterns of naming conventions, layering of styles, and separations of concerns to reduce styling side effects and bugs. In theory, being sensible about your approach to naming and using classes prevents most styling clashes. That still doesn’t ease the nervous CSS newbie dipping their toe into a well established CSS codebase - and I can see their point.

Sadly, in order to be the kind of super-efficient CSS developer we all strive to be, we need to have a complete understanding of the site we are working on. Every browser foible, every odd little @media breakpoint, JS fallback and page state takes time to understand, and just isn’t practical for every single case. This is especially true in an agency environment, where team members can change, or several months can pass between development sprints.

Back-enders have it easy.[1] They get a huge range of testing suites to pick from that will test all their code at a unit and integration level. Once they leave a project, they can offload all their silo’d knowledge into their specs, confident that the tests will serve to remind them if and when they return to the codebase.

Not so the keen Stylesheet Adventurer. No matter how closely to the BEM convention they stick, the moment they add an extended class style onto an existing module, a seed of Doubt will being to germinate in the back on their mind. Are you certain that’s not going to cause issues anywhere else?

TDD-CSS

Having back-end-like tests for CSS would provide a level of confidence for developers with their own styles. Having confidence in your code means that you aren’t afraid to rip out redundant sections or extend upon existing work from other team members.

There have been a some attempts before to solve the ‘how-to-write-tests-for-CSS’ problem, to varying degrees of success. I can’t help but feel, however, that when the success of your code is almost entirely visual, a visual solution is the most effective option.

What would be handy is a facility where a developer could get an at-a-glance overview of all styles, without needing to navigate to every obscure corner of app, or being forced to intentionally misuse a feature in order to see an error message.

In the last few years, living CSS styleguides have become very popular as a choice of development tool. A separate suite of webpages, sharing the same assets as the main site, but comprised of static HTML patterns to document use cases of CSS. The shining examples of this are Bootstrap’s documentation pages, Github’s Primer, A List Apart… and, well, all of styleguides.io

The great thing about living styleguides is that they are the tip of a massive and well-established pattern library iceberg. Let’s ignore for now the established guides we have all seen that for logo usage, voice and tone, or coding conventions. Although all are VERY necessary, they constitute only a section of what is possible. Instead, we’ll stick with HTML and CSS components.[2]

CSS Styleguides can be interfaces into your world of CSS patterns. The breadth of that interface is up to you. You may choose to simply display the types of headings, copy and colour swatches available. Or you could go deep and display every single component of your site, such as headers, cards and lists. Maybe take Brad Frost’s approach and consider an atomic design methodology; deconstruct your classes from atoms through molecules and up to complex organisms. It is entirely up to you what and how you display your components, as long as you are communicating to your team how a CSS module works, it shouldn’t matter.

Component libraries are an extension upon that idea. Instead of providing a general sense of the look and feel of an app, we go full resolution. Every class, module and component is included. This is not for the designers and brand managers. This is the reference book for the folk at the coal face. If it’s in production code, it should be here too.

It’s not simple work by any means, and like traditional spec writing, it can be seen as a bit of a slog sometimes, but once you have all these components, all on one page… Wow, things start to become very interesting.

Component library all the things

Happy path scenario: Make a global font size change in your CSS. Instead of checking on each and every page, you simply visit your component library page and scroll through to see if there are any adverse affects. Then you pick up your phone and try it on that as well. All good? Great, carry on with your day.

Need to re-theme? Need to test on an ancient browser? Need to test the registration process, but don’t want to spam the servers with fake accounts? Create static components of each state and preserve them in your library for easy checking in the future.

Create static versions of multi-step logins, or invalid form fields without having to manually go through the process yourself, every single time.

Add in some automated testing, for example with Wraith, that compares a screenshot of your current styleguide against, say that of an earlier deployment and reports back with any differences between the two.

A component library, populated well, can be your documentation of why a pattern was chosen, a sandbox for new features, a debugger and a testing tool.

We’ve been using component libraries for a couple of years now, and the results are obvious. No more ‘is that class still needed’ questions, no more creating elaborate data structures to see if an extra long peice of content breaks the layout. Glorious.

My ‘oooh yeeaaah’ moment was when I realised that I could now easily refactor a global component to take advantage of a new CSS feature without needing to create a new component class and replace HTML. I didn’t need to manually check all instances of it in production to see if it worked. I could probably count the number of times I’ve been able to refactor CSS this easily on one hand.

Having the ability to change your entire site’s look and feel, or conversely, changing the entire way your pages are constructed without changing the look and feel at all, and without having to manually check and re-check all the pages across your site? That’s pretty powerful.

I think that we should be trying to give everyone in a development team ownership of CSS development. Style guides are a step towards that; with a built-in birds-eye-view of all your CSS code, it’s possible to see all the ramifications of updating styles. If we can reduce the fears of introducing regression bugs or developing new features that collide with existing elements, then we can focus on the actual details of CSS, rather than the implementation. You know; the fun stuff!

Oh god, that’s going to be engraved on my tombstone after an angry mob of Rails developers lynch me. If I’m

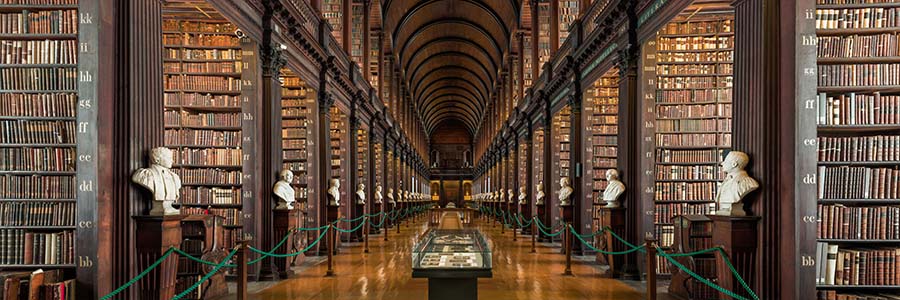

found_dead(Time.now, 1.month.from_now)please narrow the list of suspects down to known Rubymine users. ↩︎In the Global Library that is all possible types of styleguide, let us venture into the… HTML Pattern section? The CSS Components aisle? Metaphors are hard, man. ↩︎